STEP 1.

RAW MATERIAL FOR TEXTILE MATERIALS

Many different textile materials are involved when making our clothes. For example, cotton, linen, wool, viscose, and polyester often consist of mixtures of two or more textile fibres. Textile fibre is long, narrow and flexible in shape and is the primary material for fabric and clothing. The textile material is sorted according to whether they are artificial or natural and whether the raw material for the fibres comes from plants, animals or oil.

NATURAL FIBRES

Natural fibres are fibres that come from nature. For example, humans have used cotton, linen and silk for several thousand years to spin threads and make clothes. Natural fibre can be from plants, plant fibres like cotton and flax, or animal fibres like wool and silk. The appearance and properties of natural fibres vary greatly depending on their origin. For example, a cotton fibre can range from just over one to six centimetres. A silk fibre, on the other hand, is several 100 meters long and is called a filament.

Challenges with natural fibres – PLANT FIBRES

Plant and animal fibres are both natural fibres. Cotton belongs to the plant fibres and is one of the fibres responsible for the most significant environmental impact. To produce one kilogram of conventionally grown cotton from the cotton plant, between 7,000 and 29,000 litres of water and large amounts of insect and weed-killing chemicals are used. One kilo of cotton is enough for 5 to 6 t-shirts. This water-demanding plant has depleted lakes, rivers and ecosystems in the regions where it is grown. In addition, the cotton plant requires heat, which limits the number of cultivable places to areas that are often already poor in water. Another problem is that cotton is primarily grown year after year as a monoculture. Thus, it depletes the earth’s balance of minerals and nutrients and reduces biodiversity.

Flax and hemp are two other plant fibres less dependent on artificial irrigation. Therefore smaller amounts of chemicals are used. This is because hemp and flax grow in colder and rainier climates and are not as exposed and sensitive to pests.

Challenges with natural fibres – ANIMAL FIBRES

Animal husbandry for fibre use has similar problems to agriculture. So it happens that breeders use antibiotics to speed up growth and to keep diseases at bay.

The animals are bathed in bactericidal agents, an antiseptic solution, to protect against infections of wounds. The oily wool is often dirty, may contain parasites, and must be washed clean before spinning. Hot water, detergents, insecticides, solvents, and sometimes ammonia are used when washing.

Efficient wastewater treatment or a closed washing system is needed to ensure that chemicals or wool grease do not spill out in nature.

Merino sheep are a popular breed in the clothing industry for their wool. Breeders have long had problems with flies laying eggs in skin folds on sheep, especially on the hindquarters with dirt and faeces. A method known as mulesing, where the skin folds are scalped, is used to prevent such attacks. An intervention occurs typically when the lambs are between 4-12 weeks old and is considered animal cruelty. This phenomenon has decreased since it was noticed in the early 2000s but still occurs.

ARTIFICIAL FIBRES

Fibres that are manufactured artificially through chemical processes are called artificial fibres. The raw material for man-made fibres can either come from forests or other cellulose-based raw materials and is then called regenerated fibres. If it comes from oil, it is called synthetic fibre. To produce man-made fibres, a spinning solution is produced from the raw material and this is formed into long fibre threads and filaments. The filaments can be used as is or cut into shorter lengths and made curly to resemble natural fibres.

Regenerated Fibres

During the late 1800s, a way to produce artificial textiles from trees was invented. Through a chemical process, the cellulose was extracted into what is called regeneration. Long filaments were made from this renewing of the material, and viscose was invented. In the late 1990s, that technology developed further. The chemicals could now be reused using other solvents and processed in closed systems. The new material was named lyocell. Cellulose can be extracted from natural materials like spruce, bamboo and eucalyptus. Even cotton fibres are cellulose.

Challenges with Regenerated Fibres

Producing regenerated fibres requires less water and chemicals than conventionally grown cotton. However, it is an energy-consuming process. The difference between the textile material viscose and lyocell is essentially the technic used to produce the regenerated textile, whereas lyocell reuses the chemicals using closed systems. As a result, the regenerated fibre is often weaker and can give the clothes a shorter lifespan.

Synthetic Fibres

Synthetic fibres almost always come from fossil oil, which is not renewable. The chemical spinning solution is called granules. Common synthetic textile materials are polyester, polyamide and acrylic. Oil-based textile materials began to be manufactured in the first half of the 20th century, mainly because the price of cotton was high and supplies were uncertain in times of war, and a cheaper and safer alternative was wanted. In recent years, the production of synthetic materials has significantly increased. Synthetic fibre is often mixed with other materials as it is solid and colourfast.

Challenges with Synthetic Fibres

Fossil oil is usually used to produce synthetic fibres. Fossil oil comes from non-renewable sources. Both the extraction of crude oil and the subsequent processes require energy. The crude oil is purified, separated, and reformed and requires additives to become synthetic fibres (plastic fibres) ultimately. Unlike natural fibres, no water is needed in fibre production.

Synthetic fibres can contribute to microplastics in nature. For example, tiny fibres are released from textiles when washing, and the fibres not captured by the treatment plants end up in the environment. Because synthetic fibres are plastics, they are difficult to degrade, and it can take hundreds of years before they disappear. A natural or regenerated fibre breaks down in a few years.

STEP 2.

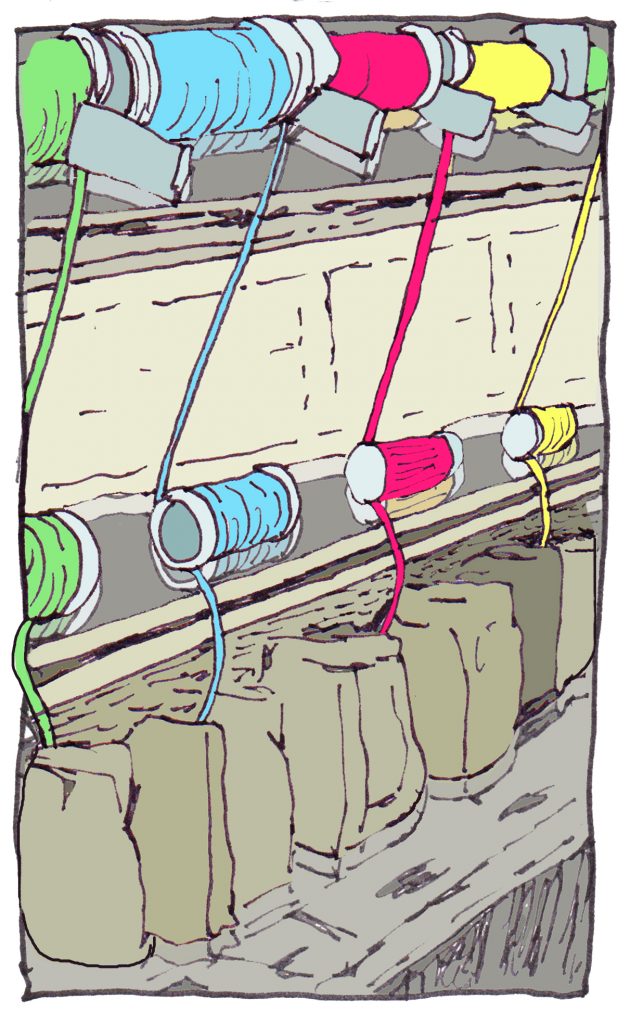

YARN MANUFACTURING

Natural fibre must first be carded to clean them and get the fibres placed parallel. The fibres can then be spun together into threads. The longer the fibres, the finer and more durable the yarn can be spun.

Regenerated and synthetic fibres can be spun into yarn like natural fibres or used as filaments. When mixed materials are to be produced, it is common for the different threads to get mixed during the carding process.

Challenges YARN MANUFACTURING

Spinning is primarily a mechanical process and requires no chemicals or water. Sometimes spinning oil is used to increase the strength of the fibres and reduce friction and static electricity.

Electricity consumption is high, however, and as production often occurs in countries that use energy sources such as coal and natural gas, greenhouse gas emissions are significant.

STEP 3.

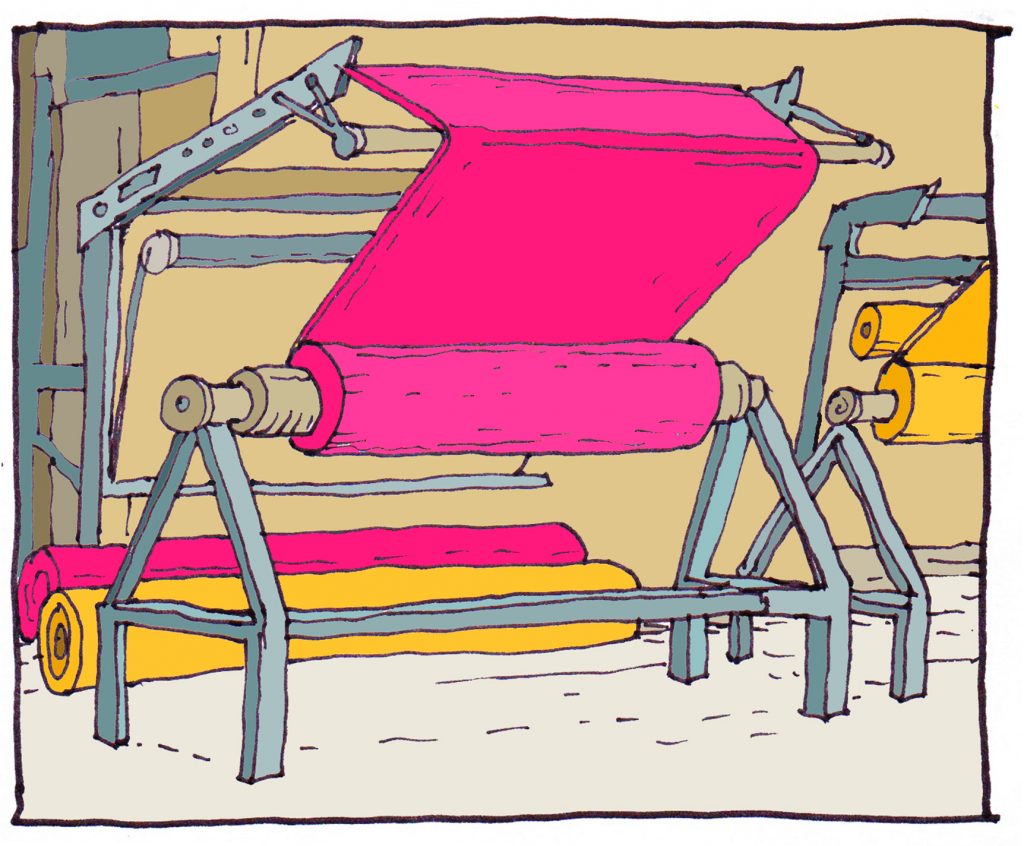

FABRIC MANUFACTURING

Once the thread is spun, it is woven or knitted into the fabric that can be made into clothing. Weaving is done by two thread systems, warp and weft, which are woven together. Knitted fabric is made by tying thread/yarn together in loops. In the past, it was woven and knitted by hand, but today, for production to go quickly, it is winding and weaving machines that produce the textiles. A modern knitting machine knits up to 300 m2 per hour.

Challenges when fabric manufacturing – KNITTING

When fabrics are to be knitted, oils and wax are used to streamline the knitting process, such as removing static electricity and reducing the friction that would otherwise wear on the threads. Some oils are natural while others are chemically produced.

Challenges in fabric production – WEAVING

Weaving is very energy-intensive. When weaving, the threads are treated with weaving glue to protect, strengthen and soften the threads so that they become pliable during the weave. The adhesive can be starch-based or synthetic.

These chemicals, knitting oils and warp adhesives are washed away before dyeing or sewing. Purification of the used wash water is therefore essential.

STEP 4.

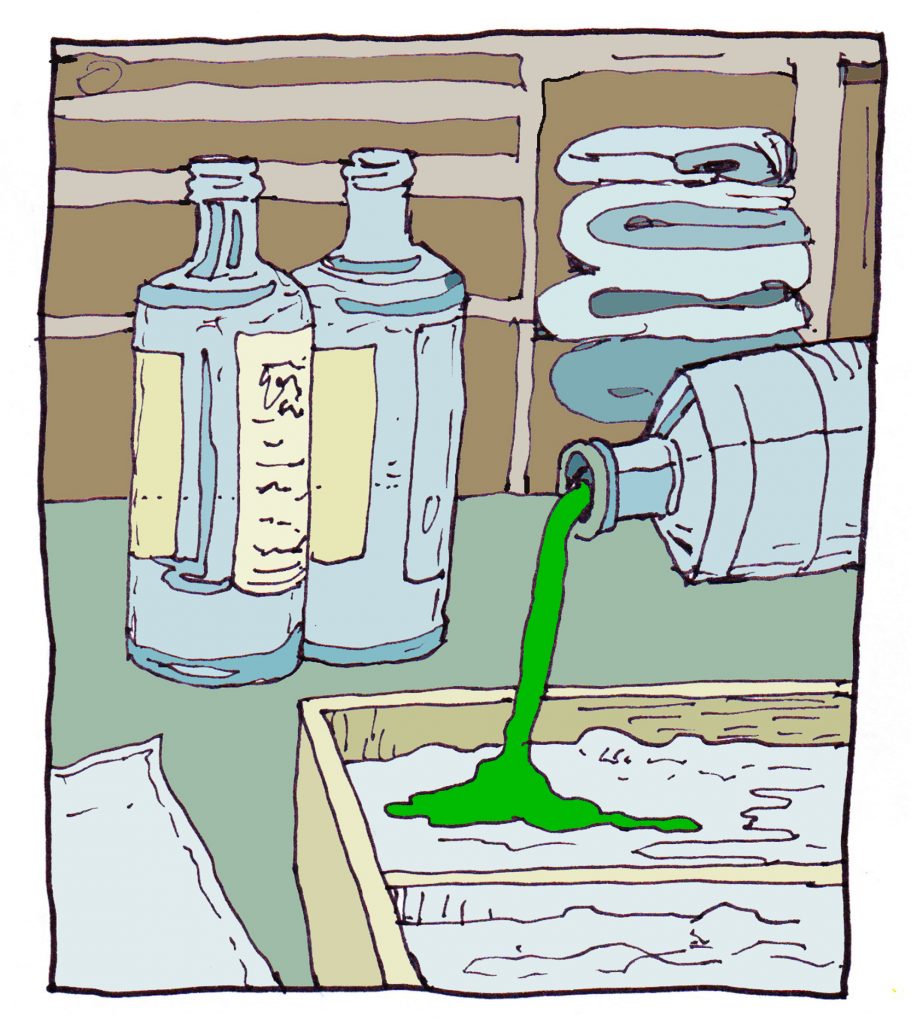

DYEING/BLEACHING/PREPARATION

For clothes to be coloured, they need to be dyed. The dyeing process can occur in all stages, from fibre or regenerated/granule thread to fabric and garment dyeing. It is common for dyeing to occur while the material is manufactured. Also, other desired effects on a piece of clothing, such as water repellency and easy care, can be added in all stages. Washing effects such as stone washing are often added in the last step, garment manufacturing.

Challenges when COLOURING

Large amounts of water and chemicals are used for pre-treatment, dyeing, washing and finishing. It also takes much energy to heat large quantities of water and to dry the materials between the processes. Dyeing takes place with dyes that are mostly synthetically produced today. In addition to pigments, auxiliary chemicals are used, for example, to fix the colour in the fabric. In the final preparation, the material can be treated to obtain desired properties, for example, softening or water-repellent treatment. It is not uncommon for chemicals used during dyeing and treatment to contain environmentally or health-hazardous substances. The processed water is sometimes released into the nearest river or lake without purification. Some waterways near dying factories in Bangladesh, for example, “change colour after the fashion season”. If the water is not purified, it can affect the natural ecosystem and harm aquatic organisms. Some chemicals do not break down but remain in nature and cause, for example, male fish to change sex to female fish – then the species can no longer reproduce. Harmful substances can also affect people working in the factory.

STEP 5.

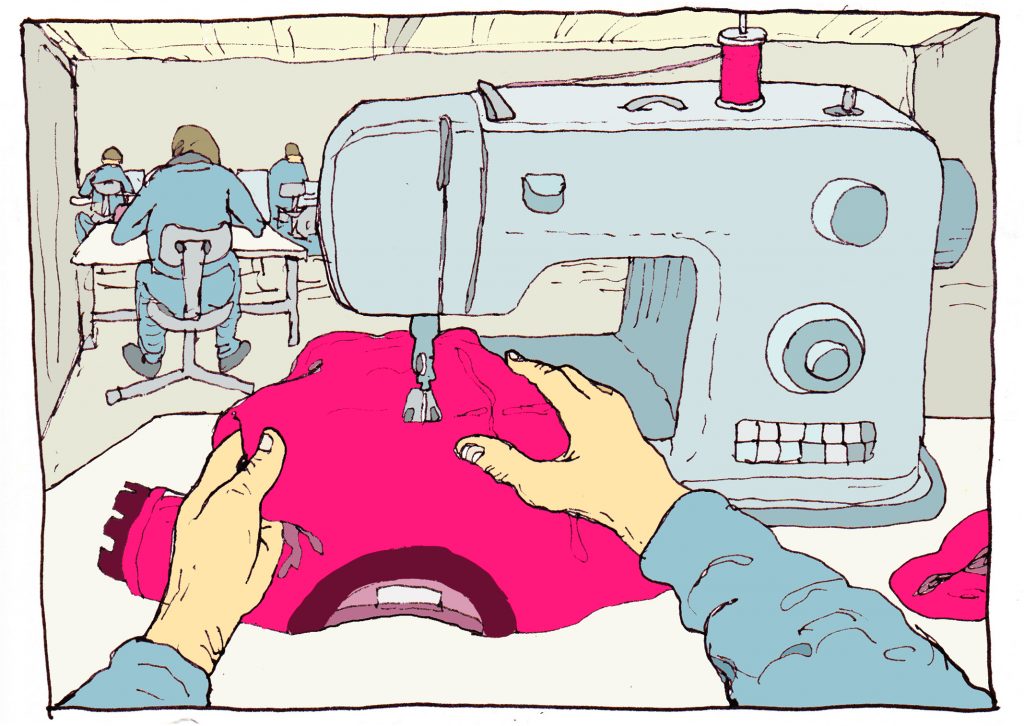

GARMENT MANUFACTURE

When the fabric is manufactured, it goes to sewing factories, where the material is cut according to pattern parts. To sew together a finished garment, in addition to fabric, various types of accessories are also needed, such as thread, buttons, zippers and labels. These are purchased from multiple suppliers.

Usually, the factories use so-called lines (“lines”) where the textile workers sew a specific part of a garment, for example, sleeves or collars. When a garment has passed through all the lines, the final garment is ready as it is checked and packed before being transported further. Today, virtually no clothes are produced in Sweden, but mainly in developing countries such as Asia such as China, Bangladesh and India, as well as South America.

Challenges CLOTHING MANUFACTURING

The sewing unit gathers the materials and accessories that must be included in a garment. Different parts can have other environmental problems; for example, metal buttons have high lead levels, or prints can contain phthalates. In addition, the various components may have been manufactured under different conditions and laws where the requirements for environmental management differ.

Planning is required to get as little waste as possible when cutting the pattern parts. Often 15 to 20% of the fabric is wasted, which often becomes waste.

When the clothes are then to be shipped, different means of transport are used depending on how far away the clothing manufacturing took place. The most common is that they are transported by boat, but it also happens that they are shipped by plane. Shorter distances are often done by truck.

In some cases, anti-fungal agents are added to prevent growth during long journeys. Unfortunately, these agents are often allergy-inducing and affect both humans and the environment.

STEP 6.

CLOTHING SALES

Depending on where the clothes were made, the finished garments are sent in bags and boxes by boat, train, truck or plane to warehouses and stores. Almost 80% of all clothing sold in Sweden is manufactured outside the EU, and the most significant import is from Asia. Today, clothing is mainly sold via stores and online shopping. In Sweden, we buy an average of 10 kg of clothes per person yearly or 1.8 garments per month.

Challenges CLOTHING SALES

In the last 15 years, the production of clothing and textiles worldwide has doubled. In principle, the entire increase consists of materials made from synthetic fibres. Synthetic fibres today account for over 60% of the world’s production of textiles. Cotton accounts for approximately 24%. Production of cotton in quantity has been relatively constant since the 1970s.

When clothes don’t sell after mark-downs, they are sometimes burned but usually, they are sent to the second-hand market in other countries.

One way to ensure that the shirt was produced in a fair way is to buy eco-labelled. Read more about independent environmental labels and certifications for textiles here.

STEP 7.

USE OF CLOTHES

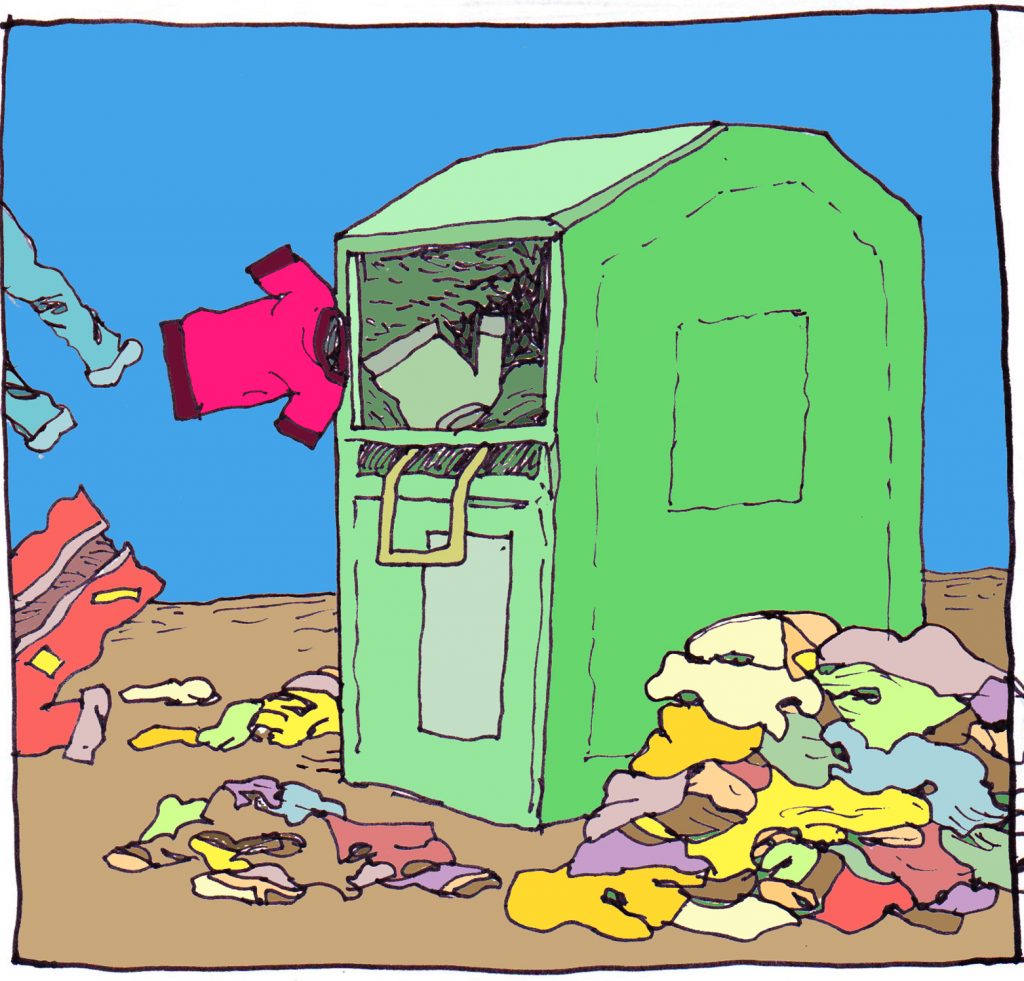

We buy large quantities of clothes every year. Much of the clothes are left hanging in the wardrobe, and about a third are never used. Of what we buy, almost 8 kg are thrown in the garbage, of which about 5 kg have turned out to be whole and clean clothes. We also give approximately 3kg per person to charities each year.

Challenges USE OF CLOTHES

The environmental impact of the manufacture of textiles is significant. For example, if the clothes are worn three times longer than the average, the garment’s climate impact is reduced by 65% and its water use by 66%, provided that no new garment is purchased.

Washing and drying wear and tear on clothes and using energy. Some washing and rinsing agents contain substances that are harmful to the environment and are not always clean. It is easy to wash with today’s washing machines, so clothes are washed even with a tiny stain. Wash off the stain or airing it would have been just as good.

STEP 8.

RECYCLING

Today, it is impossible to hand in clothes for recycling to municipal collection (except for some individual municipalities). Instead, private or non-profit actors take care of donated clothes such as Myrorna and Humanbridge. Company I:CO is the in-store collection company of several large chains. The clothes that are handed in for reuse and recycling, regardless of whether the clothes are left at recycling stations or in stores, are typically sorted according to the following categories:

• Clothes that can be sold at second-hand shops in Sweden. About 20% belong to this group.

• Clothes that can be sold in other countries, often developing countries in Africa. The clothes are packed in bales and sold to market traders who sell on to local markets. Only about 70% is exported to other countries, and 55% is reused abroad.

• Clothes torn, dirty or not believed to be salable are incinerated or used for rags, stuffing and insulation.

We need adequate technology to recycle old clothes into new fibres; the recycling company I:CO states that the figure today is around 0.1% of clothes collected.

Challenges RECYCLING

The amount of clothes that are recycled into new textiles today is estimated to be around 0.1%. This is because the technology still hasn’t been developed for a more efficient, industrial scale. PET bottles are one material that is recyclable into new textiles.

Textiles can be recycled either mechanically or chemically. In mechanical recycling, the material is cut, torn and carded to make new yarn. The result is short fibres of poor quality that must be mixed with many new fibres. In chemical recycling, the textiles are dissolved or melted to make new fibres.

However, from an environmental point of view, reusing the clothes we already have is better than recycling methods. Still, if the technology develops, there is potential in the future to take care of more discarded and torn garments and make new materials instead of making new raw materials. The environmental impact when manufacturing textiles is significant. If the clothes are worn three times longer than the average, the garment’s climate impact is reduced by 65% and its water use by 66%, provided that no new garment is purchased.